11/02/2013

Size Doesn’t Matter: contemporary Nordic architects who cross boundaries

Head north and you'll find a thriving design culture where the level of consideration given to the way things look, feel and work isn't determined by their scale. Be they housing projects, chairs or taps, the Scandinavian approach to design continues to be a more democratic one, driven in no small part by the number of Nordic architects who design beyond buildings.

In the beginning there was Alvar Aalto.

When it comes to the narrative of 20th-century Scandinavian modernism, no individual plays an as celebrated and influential a role as the Finnish architect, responsible for such landmark buildings as the Gesamtkunstwerk-like Paimio Sanatorium, completed in 1929, the Finnish Pavilion for the 1939 New York World’s Fair, and Helskini’s ice-cool Finlandia Hall, which opened in 1971.

Informed by the social and political impetus of early modernism, articulated most clearly in the activities of the Bauhaus, Aalto went on to develop a formal and material language that was less austere and machine-like than that of his counterparts, but one which shared their commitment to improving the quality of people’s lives. Yes to rationalism for Aalto, but also yes to an understanding of the human response to (and, perhaps, need for) the organic in the shaping of our material environment.

This humanist kind of modernism came to characterise Scandinavian design practice of the mid-century, with the architect Aalto as its poster boy. His co-founding in 1935 of furniture and lighting company Artek, producing such designs as the now iconic ‘E60’ stool, acts as testimony to his belief in a democratic design culture, one where society as a whole benefits from the availability of highly considered, yet ‘simple, good’ things, be they big or small.

And it’s an idea that persists today across the contemporary Nordic design landscape. A number of big-name Scandinavian architects choose not only, on a macro level, to conceive buildings, but also to apply their creative skills to the authoring of furniture, lighting and other products, such as electronic goods. Design as a thread running through, and shaping, everyday experience.

Danish architect Bjarke Ingels, who lends his initials to his Copenhagen-based office BIG, has delivered over recent years a series of high-density housing projects that set out to challenge conventional building types, not only creating a formal dialogue with their physical context, but also reworking that very topography through their scale and expressiveness. While Aalto’s Finlandia Hall takes an abstracted cue from the angular forms of an ice-swathed Arctic terrain, Ingels’ The Mountain, a monolithic apartment block located in the Danish capital’s suburbs, also references the far-flung reaches of the north. Indeed, the image of a mountain is graphically applied to the building’s elevations, in case you missed the allusion.

BIG’s 60,000-square-metre 8 House residential complex, located in Copenhagen and completed in late 2010, also goes, well, big, creating urban-density housing that exceeds the function of mere accommodation. Its diversity of apartment types, which encourages a demographic diversity, and its emphasis on communal spaces and facilities serve to foster a sense of community and shared social experience, much like Le Corbusier’s Unité d’Habitation.

But Ingels is also the BI in KiBiSi, the Danish industrial design trio who take a truly cross-disciplinary approach to the fashioning of everyday objects. From their chair for the people, the Expo Chair (produced by Hay), which was designed to seat the millions of visitors to, among other structures, the BIG-designed Danish Pavilion at the 2010 Shanghai Expo, through household item such as kitchen utensils, to electronics and bicycles, the studio approaches design in a holistic way, where the scale of the object doesn’t determine or limit the design consideration given to or, indeed, limit the meaningfulness or pleasure it imparts to its user. It’s a joined-up way of viewing the designed world.

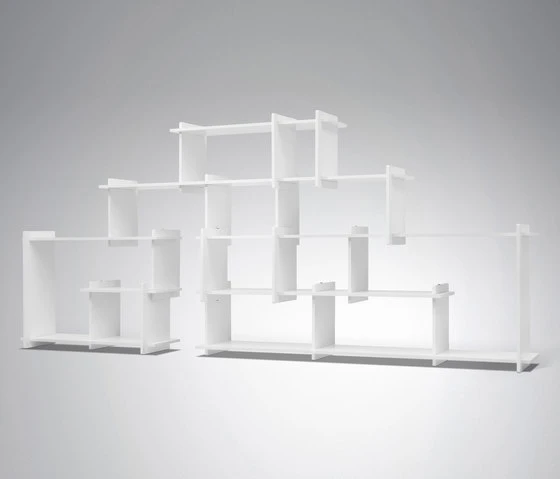

Stockholm architects and designers Claesson Koivisto Rune have a list of diverse projects under their belt as long as your arm (if you’ll excuse the mixing of metaphors). Founded as an architectural office, their activity is now resolutely multi-disciplinary, responding to a range of design briefs. While a macro-architectural definition of space can be seen in projects like their 2011 Villa Widlund – a private house in Stockholm whose exterior surface, with its conscious exposure of the joins between the concrete elements, foregrounds the building’s construction – the way that space is defined and perceived on a smaller scale is explored through such micro-architectural products as their ‘Hillside’ sideboard for Italian manufacturer Arflex, their ‘Etage’ coffee table for Swedish brand Offecct and their ‘Parcel’ storage system for Italian furniture company Former. Echoing the constructional lines of the Stockholm villa, the surface stitching on Claesson Koivisto Rune’s ‘Quartier’ set of ottomans for Tacchini reminds us of their constructedness, and how they, too, serve to punctuate the landscape, albeit an interior one.

A laying bare of the way objects are constructed can also be found in the work of Swedish office TAF Architects, whose pared-down product-design work for Scandinavian brands such as Muuto and Hay possesses a strongly utilitarian, yet friendly quality. ‘Upside Down’, produced by Hay, inverts the traditional four-legged table, revealing its usually unseen construction, and with it the beauty of such detail. Meanwhile, their ‘Wood Lamp’ for Muuto is deliberately lo-tech and approachable. Although more polished in terms both of form and material, TAF’s latest lighting design, their ‘Up’ LED lamp (which was exhibited by Muuto at this year’s Maison & Objet fair in Paris) has been designed with utility as its primary function: the lamp’s profile and its rotatable mechanism means the user can define the physical space around him- or herself by choosing where to cast light and create shadow.

The design wing of Danish architectural office Schmidt Hammer Lassen, SHL Design, which is headed up by Lars Vejen, devotes its time to thinking about how designed objects shape our experience of interior space. Beyond its numerous collaborations with Nordic brands JENSENplus, Montana, SA Möbler and FOCUS Lighting, which has resulted in a large family of rational furniture and lighting pieces, they have created the ‘Kuber’ interior-design system for One Collection, a flexible space-dividing and space-defining programme, which, with its modular, full-height panels and optional storage elements, combines the macro with the micro. Things small but important in everyday life are considered by fellow Danes Aarhus Arkitekterne too, who have created a range of bathroom fittings for Danish manufacturer Vola, which continue the language of formal reduction that design legend Arne Jacobsen established for the company with his taps from the 1960s.

Helsinki office Vesa Honkonen Architects and Copenhagen-based practice Space also work in a decidedly multi-disciplinary way, both having authored in addition to a variety of architectural, interior and public-space projects numerous furniture and products for the likes of Louis Poulsen, Källemo, Blond Belysning, Stellarworks, Mater and Howe.

Thomas Sandell of Stockholm architectural office sanddellsanberg, meanwhile, applies his creative thinking to an even broader approach to the design of our material world, choosing to work in textiles and outdoor products as well as furniture and lighting. Asplund, Offecct, Lucente, Leucos and Nikari count among his diverse list of clients. But it’s perhaps his ‘Lighthouse’ indoor and outdoor lamp for lighting brand Zero, however – which takes, in miniature, the archetypal form of a Western house, replete with pitched roof – that says the most about the Nordic design mentality, functioning as, among other things, a metaphor for the continued engagement in Nordic creative practice with good design for the many, across disciplines. For Scandinavian architects, scale is no object to design that works and pleases.